The government has abandoned its efforts to build a centralised coronavirus contact-tracing app after nearly three months, announcing it will instead switch to the model preferred by the technology firms Apple and Google.

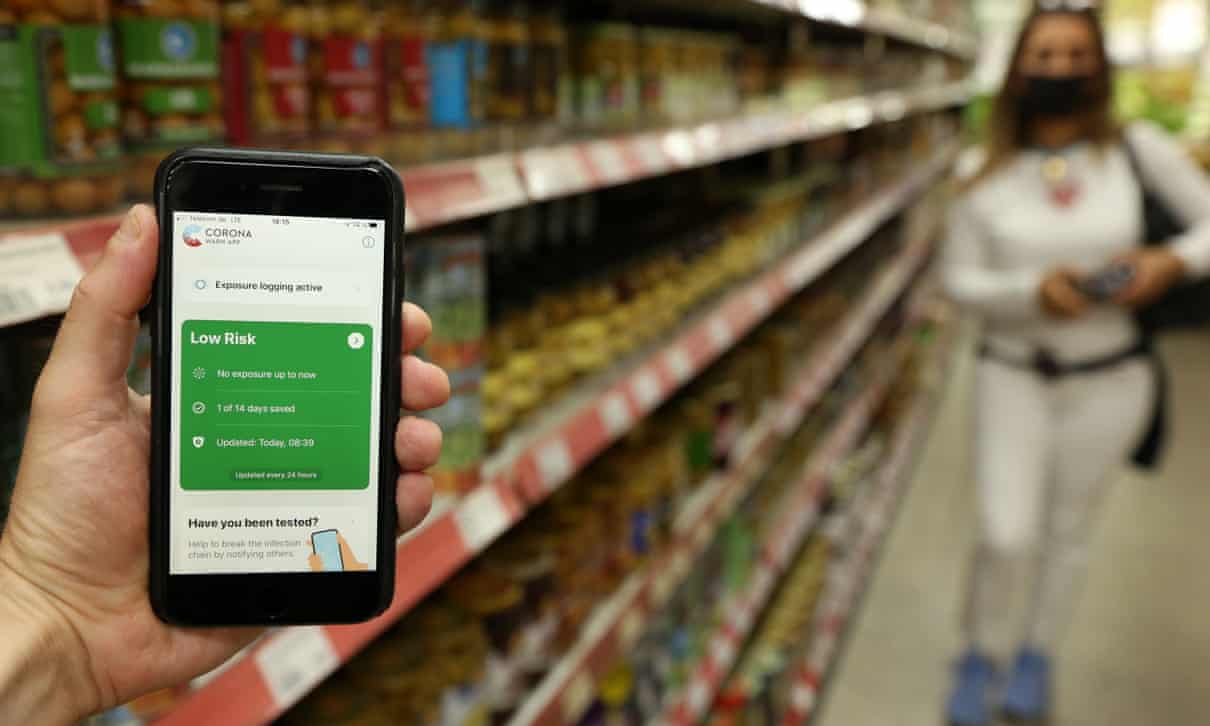

The move is another embarrassing U-turn for the government in its management of the pandemic, but what is it all about?What is a contact-tracing app?Contact tracing is a crucial part of a "suppression" strategy for managing Covid-19, in which the health service tries to keep new cases as low as possible for as long as possible. By tracking down everyone a newly infected person has been near and advising them to self-isolate before they too potentially become infectious, the chain of transmission can be broken, preventing further infections.A contact-tracing app attempts to automate some of that work by using the technology in smartphones to automatically record who you have been close to. The advantages, if it works, are clear: the app can track contacts who you may not know personally, eg, those you came close to on public transport, in bars and restaurants, or in shops; and it can speed up the work of notifying tens or hundreds of people at once that they may have been exposed to Covid-19.How does it work?All major approaches to contact tracing have used the Bluetooth wireless radio to try to track nearby phones. By constantly sending out a unique, anonymous signal, and listening to other signals being sent out, a phone can build a sort of address book of all the other people it has been near. Then, if its owner comes down with Covid-19, the app can send a warning to every phone it recently heard from.But there is one major split in approaches, about whether that warning should also be sent to the health services of the country. Under the approach the UK government had been trialling until Thursday, the NHS would have acted as a centralised body, receiving the warnings and passing them on to all other phones. That would have given the government much more visibility on the spread of the disease, and allowed it to implement tighter security to prevent malicious use of the system. However, the potential overreach of this approach concerned privacy campaigners.What went wrong with the government app?Always sending messages over Bluetooth chews up phone batteries, and can, if done maliciously, prove a major security hazard, so both Android and iOS, the two main operating systems, limit what apps can do with it. That means that, in the first version of the government's app, contacts were only successfully recorded 75% of the time for Android phones, and just 4% of the time for iPhones, which have a much stricter set of restrictions.How did Apple and Google get involved?Apple and Google worked together to build a new set of tools that governments around the world could use to avoid those restrictions, which they announced in April and released a month later in May. But apps built using those tools have to operate in a "decentralised" way, giving up access to the data which the NHS hoped to use, leading to two months of standoff.Are the problems all fixed now?One major issue remains, which has plagued not only the UK's tests, but other contact-tracing apps around the globe: the Bluetooth signal on which the app depends is a very unreliable way of estimating distance. This means that two phones kept in pockets on a crowded train can "think" they are very far away from each other despite being within 2 metres, while two phones in active use outdoors can "think" they are very close, even if they are in fact well out of the danger zone.Unless that problem is solved, contract-tracing apps will give far too many false results, either advising people to isolate who are at no risk of spreading coronavirus, or allowing people to think they are virus-free when they may in fact be spreading it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment